The Global Water Integrity Outlook was launched in The Netherlands on 15 April 2016.

Published on: 11/05/2016

Every year the water sector loses US$ 75 billion through corruption. That is a conservative estimate as there is still no reliable data, says the director of the Water Integrity Network (WIN) Frank van der Valk. Corruption undermines our ability to assure water security, leaving the most vulnerable at risk. Mr. Van der Valk was in The Hague to launch WIN’s flagship publication, the Global Water Integrity Outlook, at an event co-organised by IRC in cooperation with the Dutch Water Authorities (DWA), the Netherlands Water Partnership (NWP) and the Global Compact Network Netherlands (GC NL).

"Ensuring integrity requires strong systems", said IRC CEO Patrick Moriarty at the opening of the WIN-IRC event. Mr. Van der Valk supported this view by saying that programmes should invest first in systems before installing pumps. WIN Association board member Henk van Schaik added that the ethical dimension of integrity deserved more attention. Leaders with a strong sense of ethical and moral values are great integrity ambassadors.

Many organisations and programmes are “corruption blind”, Van der Valk said. They don’t see it or they don’t want to see it. Courage is needed to report corrupt practices. Whistleblower Ad Bos, who exposed grand corruption in the Dutch construction sector in 2001 “lost everything except his wife”, Herman Havekes, strategic advisor for the Dutch Water Authorities (DWA) told the audience. Bos’ revelations saved the Dutch state an estimated 1 billion euros, but he had to wait 8 years before he was rehabilitated. Only this year, 15 years after Bos spoke out, has The Netherlands finally passed legislation on whistleblower protection.

That was the title of a 1988 evaluation study by the Scandinavian Institute of African Studies on a decade of donor funding to rural water supply in Tanzania. The conclusion was that the donors' '"approach [focus on construction while ignoring maintenance and local capacity development] has significantly contributed to the non-use of their plans and non-sustainability of the schemes". Listening to the presentation by IRC's Catarina Fonseca, you can only conclude that little has changed. Close to half a billion dollars has been pumped into Tanzania's national rural water supply programme (2007-2014) and coverage (officially 45.5% in reality lower) has not increased since 1990 but is actually declining.

Unfortunately most evaluation, mid-term reviews and costing reports in the sector are not made public. https://t.co/FVGzvZBah1

— Catarina Fonseca (@ircCatarina) April 14, 2016

Ms Fonseca's showed photos of water systems, often over-designed, which all stopped working after a few years because they weren't repaired or the supply of fuel dried up. She was part of a team involved in a value for money study of the UK government's £ 30 million (US$ 44 million) contribution to Tanzania's rural water programme. The team found that it was impossible to track how and where money had been spent at the district level. Data on the functionality of rural water points was inaccurate and of poor quality. Based on her experience, Ms Fonseca finds that governments are reluctant to share financial data. "This seriously undermines accountability for the funds spent in the sector", she said.

The Tanzanian government's performance-based Big Results Now (BRN) initiative was designed to fast track development in six priority areas of the economy, including water. BRN promised to increase rural water coverage to 67% by 2015/2016 but a national survey conducted by Twaweza in September 2015 found that only 41% of the rural population was using an improved water source and that 80% of the respondents had not seen any improvement in coverage or access.

Kees Rade, head of Inclusive Green Growth at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, was shocked to hear that after 30-40 years of development aid projects are still being implemented without giving proper attention to sustainability. He emphasised that Dutch-funded water projects are required to ensure that systems are still working 10 years after projects conclude.

The Dutch take great pride not only in their flood protection works but also in their decentralised water governance model. Good water governance is a prerequisite for the prevention of fraud and corruption, concluded Herman Havekes. The 23 self-supporting regional water authorities collect € 2.7 billion (US$ 3.1 billion) annually in water taxes, which largely goes to private sector contracts for maintenance and construction works. When that amount of money changes hands integrity is at risk.

The Netherlands has a set of legal provisions to prevent corruption such as the aforementioned new whistleblower protection act. Worth mentioning as well is a 2016 amendment to the regional water authority (RWA) act that makes RWA chairs personally responsible for integrity within their organisations. Next to legislation, water authorities have a renewed code of conduct, an integrity toolkit and water sector benchmarks at their disposal. Job rotation for financial controllers is obligatory after 10 years.

The United Nations Global Compact (UNGC) is the most popular corporate responsibility initiative among businesses, with 8,610 corporate and over 4,000 non-business participants, including a large membership base in developing countries. Signatories to the Global Compact commit to report on their efforts to follow 10 principles on human rights, labour, environment and anti-corruption.

One of the UNGC's initiatives is the CEO Water Mandate on corporate water stewardship, whose members collaborate with non-profits via the Water Action Hub.

Jeroen Kool of the Global Compact Network Netherlands (GC NL) elaborated on how water integrity supports the objectives of the UNGC and will lead to better performance of the water sector. This fits in well with Henk van Schaik's plea to develop a business case for corporate water integrity.

Not so long ago, offering bribes to foreign public officials was seen as an unavoidable and perfectly acceptable way to win contracts. Up to 2004 paying bribes abroad was still tax deductible for Dutch companies. So what has lead businesses to embrace corporate responsibility and develop anti-corruption policies? It can be partly attributed to the introduction of the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention but the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) has arguably had a greater impact. This Act allows the US to slap hefty fines on both American and foreign companies. On top of that, corrupt foreign companies risk exclusion from the US market.

As a voluntary initiative, the aim of the UNGC is to support corporate responsibility, not to police or enforce it. The only obligation for participating companies is publication of an annual Communication on Progress (COP). Participants that fail to communicate progress are downgraded to "non-communicating". If this happens for two years in a row, participants are marked "delisted" but remain on the web site. To date the UNGC has expelled nearly 6,300 participants.

The UNGC has been criticised for merely promoting good intentions. Indeed, in their 2011 article "Ethical breakdowns", Bazerman and Tenbrunsel concluded that unethical behaviour was on the rise "despite all the time and money that have gone toward [ethical] efforts, and all the laws and regulations that have been enacted". The good thing about the UNGC website is that company self-reported COPs are counterbalanced by linking them to information collected by the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre.

Zero tolerance

The Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs has a zero tolerance policy towards corruption and bad governance, Kees Rade said. It is immoral and illegal to misuse funds meant for water and sanitation projects. Therefore, at the first sign of misuse of funds, projects are suspended as was the case in 2015 in Benin, Mr Rade added. Only after the government of Benin repaid the € 4 million that the Ministry of Water had embezzled and initiated anti-corruption measures, did The Netherlands consider funding a new water programme.

Another, maybe even more important reason for zero tolerance is that corruption undermines public support for development cooperation. In a 2015 national survey, the main cause of poverty in the world, according to the Dutch public, was corruption and bad governance.

Despite widespread corruption in the water sector, it is not all doom and gloom. Even in corrupt environments, "clean" initiatives are possible. The Global Water Integrity Outlook mentions several of these "diamonds":

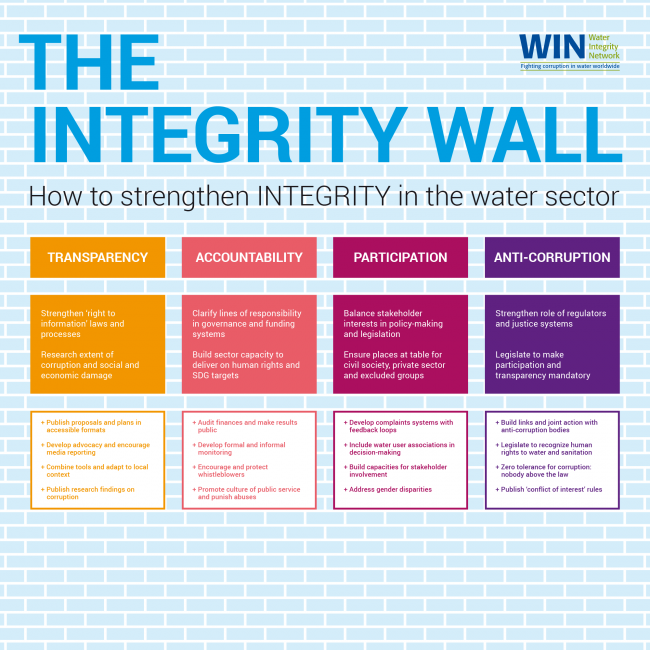

The Global Water Integrity Outlook is a call to action for everyone working in the water sector. Donors, companies, government and civil society, all need to take up their responsibility. Courageous people who promote integrity in countries where corruption is rampant deserve our support. The Water Integrity Network has a framework – the Integrity Wall – and the Integrity Management (IM) Toolbox to guide our efforts. Success depends on the strength of the ethical and moral values of those who implement them.

View below a video impression of the WIN-IRC event including short interviews with Frank van der Valk (Water Integrity Network), Kees Rade (Ministry of Foreign Affairs), Catarina Fonseca (IRC), Herman Havekes (Dutch Water Authorities), Jeroen Kool (Global Compact Network Netherlands/WaterPartners Foundation) and Elema Humphreys (UNESCO-IHE).

You can find links to the full Global Water Integrity Outlook and the WIN-IRC Event presentations listed below under Resources.

Acknowledgement: this blog draws from the Dutch news release "Nederlandse watersector is corruptieblind over de grens", Waterforum, 20 April 2016.

At IRC we have strong opinions and we value honest and frank discussion, so you won't be surprised to hear that not all the opinions on this site represent our official policy.