The unprecedented flood of August 2018 has put Kerala on the spot. Integrated water resources management will have to be a key pillar in managing the recurrent floods and droughts.

Published on: 08/10/2018

This blog has been co-written with V. Ratna Reddy, former Director of CESS, Hyderabad and currently the Director of the Livelihoods and Natural Resource Management Institute.

Most Indians cherish Kerala as 'God's own country' with high social indicators and mature decentralisation. But not many are aware of its degrading natural systems like river basins and ecosystems. Though the State is rain rich, it is water poor. The projections of both the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) and the World Resource Institute (WRI) predict bleak water prospects for Kerala. With an average annual rainfall of above 3000 mm, it faces severe drinking water problems in quantity as well as quality for most parts of the year. Apart from high precipitation, Kerala is rich in surface resources like rivers (44 in all) and canals, wells, tanks, ponds, etc. But, sub-surface topographic and geomorphic settings of the State allow the utilisation of only a small portion of the surface resources. The aquifers are not only limited by recharge capacities but also in quality, constraining the optimal development of available resources. Any plans for rebuilding Kerala will have to include integrated water resources management (IWRM) as a key pillar for building climate resilience and managing recurrent floods and droughts.

Kerala rivers during and after the monsoon

Hitherto, the policy approach to water resources has been sectoral, infrastructure and supply driven, which has not been effective in addressing even the strident problem of drinking water scarcity. For instance, despite a cumulative investment of over Rs. 18000 crores by KWA (Kerala Water Authority) only less than 40 percent of the households have access to piped water and the remaining 60 percent depend on open wells based self-supply. Both sources have quality issues. While faecal contamination is widespread in the case of open wells, effluent contamination is common in surface water sources (rivers and lakes). Most of its water resources are reduced to a cocktail of pollutants. Absence of river basin and groundwater management practices are the main reasons for this. Water is both an economic good and a common property resource. The State needs to make a U-turn, back to source sustainability, both in quantity and quality.

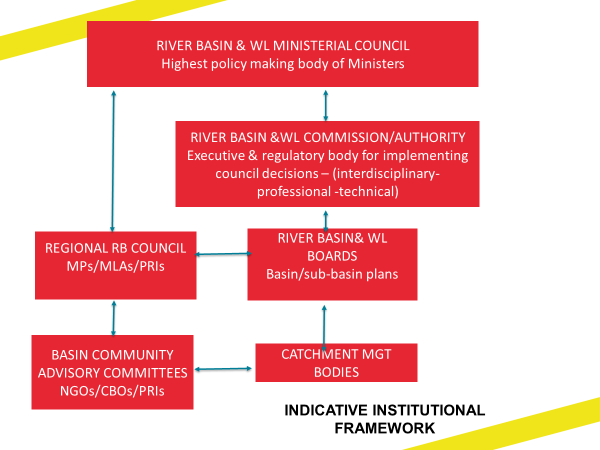

It is hard to find IWRM in practice across the world. Putting it into practice requires an evolving and contextualised approach supported by a high degree of political commitment. IWRM requires a well-thought-out institutional architecture that is decentralised, empowered, accountable and functional. Often IWRM implementation is marred by 'top-down' institutional approaches, whereas 'bottom-up' institutions would be more effective. Kerala has the advantage of effective 'gram swaraj' (successful decentralisation scheme in Kerala). Decentralised local government institutions need to take the lead with support from middle and top-level institutional arrangements. At the top-level, convergence of all water resources related institutions (departments) is critical. The State shall see the big picture, as most of our siloed interventions have far reaching 'unintended consequences' that are at times counterproductive.

Kerala's rivers are too small for creating feasible basin authorities for each river. It is suggested that all the 44 rivers may be grouped as sub-systems of a single Apex River Basin and Wetlands Authority with River Basin Boards and Catchment Management Agencies (CMAs) with key roles for basin communities and local governments. Creating institutions will never serve any purpose, unless the institutions are empowered and made accountable. The Authority, to be effective, shall be vested by overarching and cross cutting powers for basin planning and answerable only to the River Basin Apex Ministerial Council.

The unprecedented flood of 2018 could be a great opportunity to do things differently and build a better future for all in Kerala.

At IRC we have strong opinions and we value honest and frank discussion, so you won't be surprised to hear that not all the opinions on this site represent our official policy.