It is not a problem of insufficient funding, but rather a lack of creditworthiness of the sector

Published on: 07/12/2023

I took part in the roundtable on financing water in Africa co-organised by the OECD and the AfDB in Abidjan from 22 to 23 November 2023. Around fifty experts took stock of the issues, challenges and solutions for financing SDG6 in Africa. With 7 years to go, given the pace of progress, the majority of African countries will not be able to achieve universal access to basic drinking water and sanitation services by 2030. And yet the ultimate ambition is to provide the majority of the population with services that are safely managed.

From the point of view of water professionals, the real problem for several years has been insufficient funding. Most countries have plans and financial estimates for achieving the SDGs for drinking water and sanitation, but these tools are not enough to attract more funding. Many countries are calling for an increase in official development assistance, but it has to be said that these efforts will not change the trend of a significant continued reduction in ODA over the coming years.

The financial institutions, which essentially offer both grants and repayable funds (concessional or commercial), for their part, blame the limited number, narrow focus and poor quality of the investment projects presented by the countries for the sector.

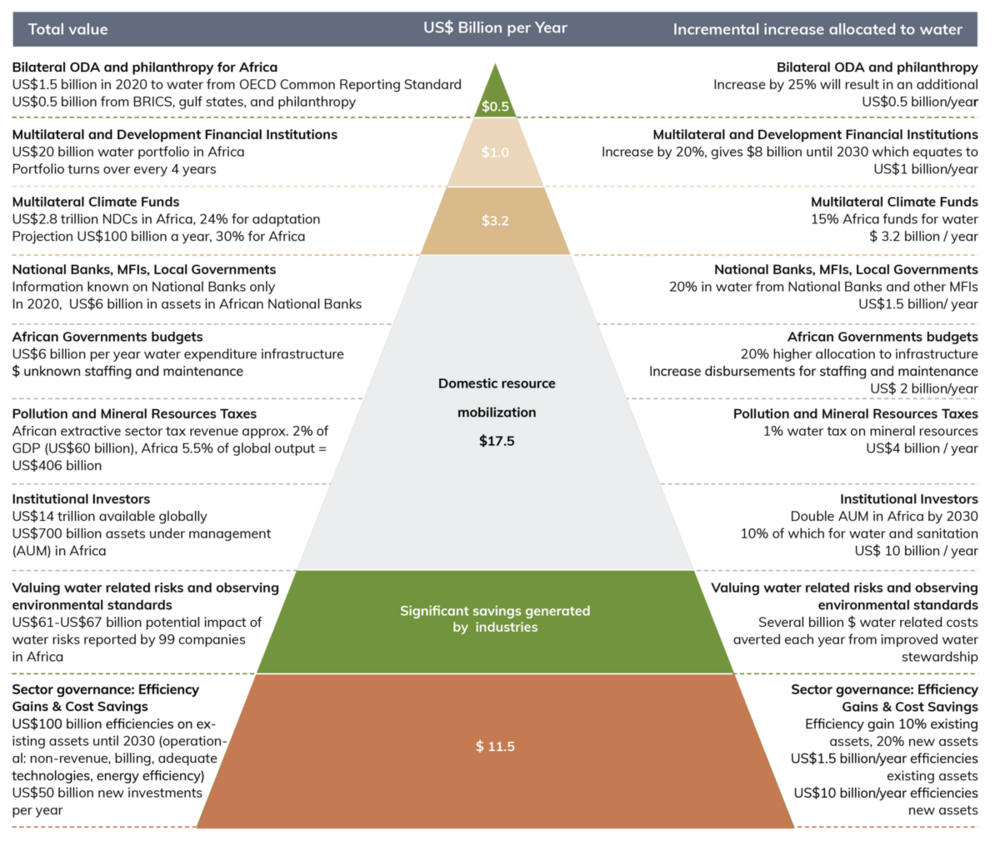

In the midst of this debate on the real obstacles to water financing, the AIP (Continental Africa Water Investment Programme), set up by the African Union Commission, has developed a pyramid for water financing that proves what other organisations in the sector have been saying for years. The base of this pyramid shows the impressive potential for improving the sector's financing through legal, institutional and organisational reforms in the sector and the mobilisation of domestic resources that can meet up to 86% of financial needs on a yearly basis. The expected contribution from financial institutions would be 8.3% and that of official development assistance only 1.6%.

Source: Africa's Rising Investment Tide: How to Mobilise US$30 Billion Annually to Achieve Water Security and Sustainable Sanitation in Africa, International High-Level Panel on Water Investments for Africa, South Africa, March 2023.

The roundtable was an opportunity for Benin (represented by the Director General of the National Agency for Drinking Water in Rural Areas) to share its recent experience, which illustrates the rationale supported by the AIP. Thanks to the political leadership of the Head of State, the country has undertaken legal, institutional, regulatory and organisational reforms that have enabled it not only to increase its domestic resources and mobilise resources from international financial institutions to cover investment needs, but also to attract international private operators for the professional management of drinking water services. According to the Director General, the country has thus been able to increase the coverage rate from 54% (in 2019) to 76.7% (in 2023) and set up services managed by professional operators throughout the country in both rural and urban areas.

These factors lead us to a first important conclusion: it is time and imperative to change the way we talk about the problem of financing water. It is not a problem of insufficient funding, but rather a lack of creditworthiness of the sector (not just of service operators such as utilities but also of public authorities). This change of narrative is essential if we are to focus our energies on the solutions that are needed and determine who is responsible for implementing them.

The national reforms needed to make the sector more attractive and creditworthy are generally identified under the headings of enabling environment, capacity building, institutional development or systems strengthening. These reforms have been known and recommended for several decades, an important benchmark being the African Water Vision 2025, which dates from 2000. These reforms have been included in all the declarations and commitments made at the highest levels by African leaders for at least 23 years. All the governments are committed to them, and all the donors (ODA) have contributed to them in various ways over these decades. It is therefore legitimate to wonder about the causes of the persistent problem of attractiveness and creditworthiness of the sector to date. One of the shortcomings of initiatives to upgrade the sector is that they are not directly indexed to a precise state of creditworthiness in the sector. Furthermore, any weaknesses in the sector's management and governance systems are interpreted as credit risks by financial institutions.

However, relevant experience of credit ratings for international financial institutions exists and is well established as a guiding tool. In the water sector, the World Bank has developed and tested a framework for analysing the creditworthiness of urban drinking water utilities, with several levels of creditworthiness. It goes without saying that water investment projects submitted by operators, countries or municipalities to national, regional or international development banks are subject to a creditworthiness assessment. But unlike international financial ratings such as Standards & Poor's, Fitch or Moody's, there is still no collectively recognised rating in sub-Saharan Africa of creditworthiness of a service authority in a defined service area. Such a service authority credit rating would not only include predicted tariff revenues generated by utilities or service operators, but also government’s contribution from, for example, tax revenues. Assigning such a credit rating to a service authority would characterise the prospects of repayment of their commitments to their creditors - suppliers, banks, bondholders, etc. - in the event of a default.

The absence of such a rating system limits the ability of service authorities to be aware of their ability to attract loans and to bring themselves up to standard. It also limits analysis of the effectiveness of support and measures to strengthen the enabling environment, build capacity, develop institutions or strengthen systems.

I therefore propose that Africa's regional development banks lead the initiative in periodically rating the creditworthiness of service authorities (at district, regional or national levels) for their water financing needs. This rating should be published, and the criteria used could serve as a framework for rationalising progressive upgrading actions (systems strengthening).

Concluding, there is a need for a change of narratives on the problems of water financing. The problem is not a lack of funding, but rather the sector's lack of ability and capacity to attract such funding, which is in turn linked to the lack of any mechanism for providing an assessment of “whole service-area authority’s creditworthiness” for financing institutions, investors and the private sector. The introduction of a transparent public rating of the creditworthiness of the main service-areas authorities in a country, led by the regional development banks would, therefore, be an important tool to support the match of supply and demand for finance.

At IRC we have strong opinions and we value honest and frank discussion, so you won't be surprised to hear that not all the opinions on this site represent our official policy.